On The Knees Of The Gods

by J. Allan Dunn

Illustrated by Manuel Rey Isip

Originally published in Unknown, February 1940

Part 3

Read Part 2

Read Part 1

VII.

THE ONE eye of the monster glowed like a hot coal in his low brow, high ridged above his flattened nose set with wide nostrils that opened and shut as he glared at Peter, snuffling.

He thrust out his tongue between tusks like those of a shark and saliva dripped from his thick lips. He did, or could, not speak, but his greedy grunt needed no translation. His sinewy, furry arms shot out with clutching fingers. His fixed gaze was that of a beast that has cornered its prey, and gloats in the prospect of fresh blood, hot flesh and bones with the marrow alive within them.

His breath stank like a bear's.

Peter skipped back, nimble as a lizard. The Cyclops followed and Peter dodged into a deep crevice with the ogre panting after, back to the light, his bulk shutting it out, with his eye gleaming fitfully. Peter was cornered.

Peter switched on his flash torch, sent the bright ray full into the Cyclops' solitary orb. It dazzled him, startled and scared him as he back up, blinded by the beam.

In his fear he forgot the narrowness of the ledge, with the electric spear of light that bewildered his sluggish brain. He went over the ledge backward with a croaking gasp, hurtling down to crash upon the floor, to lie motionless, as Peter, with his torch still on, came out of the crevice and looked down at him.

Hephaestus set down his jug and shouted: “Who comes unbidden to my realm?"

Peter called back. “One who is upon a mission for Zeus, O Great Hephaestus. One who would have speech with thee."

Peter had long ago decided that the gods all liked a little "yessing," a show of obeisance and recognition of their highness. He turned the lens of his torch to the ledge and made his way down and along it. On the floor of the smithy he could see where he was going.

He tucked the torch' away. It might come in useful again when he was looking for Python, and he was not minded to have Hephaestus take a fancy to it, expect it as a gift.

Hephaestus waited for him by his anvil. The fall of the Cyclops and his probable death did not seem to bother him. He stared at Peter, who stared back, conscious that his shadow was pretty plain. But he was tired of playing he was a god. He had determined to talk turkey to Hephaestus, come what may.

“So," said Hephaestus, “Zeus sent you—a mortal-on a mission to me? And you arrived. Now, by all the gods, you have stout entrails, earthling!"

"My task, that Zeus has charged me with, leads me here, Hephaestus, rather than I was told to come by Zeus. I find the mission has its complications."

"Ha! It seems you have a ready wit, earthling. And by the color of your hair you should have fire in your ancestry. One of those complications, I take it, was the hurling down of my guard, Zukon, from the ledge. By the way he lies, I think he is dead."

"He did not want to let me pass," Peter said simply.

"Ho, ho! And so you slew him. And he could have eaten you at one meal and still be hungry. How did you slay him? Did Zeus give you some spare thunderbolts? I make them for him, you know."

"I blinded Zukon with a light I can produce at will, like this."

PETER HAD SLID his flash torch up his sleeve. Now he lifted his arm, grasped it with one hand and pressed the contact through the cloth. The beam seemed to be coming from his other, outstretched hand. He merely flashed the light once. Hephaestus: blinked.

“You have powers above many mortals. What is your name?"

"Peter, or Petros."

“You were not afraid to come down here."

"Not after you laughed when you drove out-your Cyclopes. A man who laughs may be trusted."

"You have sound sense for one of your age. Those louts! I cannot get one of them to show any cleverness. My metals need good tempering. The fool at the bellows has no more sense than to blow like a tempest: when he should merely send a zephyr, through the coal, fan the flame like a butterfly's wing might fan; it when the iron needs forced draft: I cannot watch him all the time. I cannot give him intelligence any more than nectar mia be made from vinegar."

Peter. looked at the great bellows. An idea came to him.

"If you could regulate the draft at will, Hephaestus?”

"I am not. Scylla. I have only. two arms."

“If the bellows should be arranged so that they would work by being .fastened to a beam, and that beam attached to a pedal that could be worked by your foot—"

Hephaestus was swift in thought as the Cyclopes were slow. He immediately caught the general drift of the idea that Peter had seen used in many a smithy.

“Say that again, earthling. It sounds good."

Peter demonstrated with gesture, by a sketch he burned on a plank with a hot iron, lastly with a crude pattern. "In that way," he said, "you would not need a helper for your own delicate inventions when you forge them,” he wound up.

"By the blood of Typhon, something lives beneath that red thatch, on your poll, Peter!. That is an idea. worthy of myself. Ask me a boon in return and it is already granted. Now tell me of your task.”

"It's a long story," Peter said. He decided to come clean with Hephaestus. There was a rugged some thing about the fire god that appealed to him. If he had not been a god, Peter would have rated him as being eminently human, of good wit and understanding.

He started at the beginning and left out none of the essentials, though he avoided embroidery. He said nothing about Pan's wood nymphs or Amphitrite's fondling. Hephaestus listened with interest in."

"Have a drink,” he said. “You will find it good, though it is not nectar. I once gave Cheiron almost a third of a chalice of that. It quite upset the old boy: He thought he was a colt. I can see him now, galloping away and jumping everything in sight. He was gone for half a moon, and when he came back he looked like the wreck of the Argo. Now tell me about those horseshoes. For an earthling you have a most ingenious mind."

Peter decided to be modest.

"The horseshoes and the bellows are matters I have known in my own country," he said, and saw he had made a hit with Hephaestus.

"I could use you as an apprentice," he said. "Those Cyclopes of mine are little better than idiots, though at times they amuse me. Did you see them scoot into their holes?" He poured more wine for both of them. It was heady. Peter blocked a yawn.

"You need sleep and rest after that voyage, my lad. But now I watch while I try my hand at a horseshoe and some nails. Let us see if I have got it right. You will have to work the bellows. Later I'll rig it as you suggest."

THE FIRE GOD worked like a magician, his movements too swift for the eye to follow, the tattoo of his deft, sure blows ringing fast as the drilling of a hungry woodpecker on a well-lardered tree. In no time he had shaped a shoe, pierced it for the holes, plunged it hissing into a pot of water, held it up for Peter's inspection.

Peter suggested a slight change in shape and told Hephaestus about turning up the calks.

The godsmith nodded.

"Now for the nails," Peter said. "They should be soft metal, not to split the hoofs, and they must not rust. And the shoes must be of different sizes.”

The nails bothered Hephaestus a little, and Peter could not help him. But the problem was solved at last.

"These are simple things to make, Peter. How many does Cheiron want, think you?

"I do not know how many centaurs there are."

"I do, and I am not supplying all of them. Not at first, not without some compensation. Do they charge much for these in your country, Peter?"

"It depends." Peter told him the story of the man who agreed to the smith's bargain of one copper coin for the first hole, doubling it for the next, and so on. "He called it off with the second shoe when he found the cost was nearly thirty-three thousand coins," Peter said.

Hephaestus roared, slapped Peter on the back. "I am no good at figures," he cried, wiping his eyes. "They make my head ache. And Cheiron will have to pay me in some other way. I have found him useful before, and may again. I will furnish him enough for fifty, with a special set for himself. Who will teach them how to put them on?"

"I can do that," Peter said, "if Cheiron will make them stand: quietly. It is really best to put them on hot, then the shoe sets smoothest. You rasp off the ends of the nails, smooth the hoof."

"Cheiron will make them stand. And you may be sure the old fellow won't use them on his own hoofs until he sees how they work out with the rest. You are quite a genius, Peter did not thank him for the my lad."

Peter did not thank him for compliment and Hephaestus looked at him keenly.

"Something worrying you?”

"I don't know that I should worry about it. I am in for it, anyway. It's the idea of Zeus, his headache. I suppose he's responsible, if he ever feels responsibility for his own performances.. But I don't quite like the idea of robbing Python of his property."

"Think nothing of it. The scaly. rogue stole it himself from the Colchian witch, Medea. But that is an old tale. Now Hera will flaunt it.

And it will cause trouble in Olympus, that gem. Are you perchance married, Peter?”

"No.”

“Ha! I am. It is not all bliss. Women are like perfumed flowers with thorny stems. Press them too closely and the thorns get under. your skin You had best watch out for Ephryne. It is the general custom for a rescued maid to wed her champion. And if Ephryne gets that idea in her head, you might have trouble getting it out. Unless, of course, the idea suited you. Women are wily when they want anything.

Ask Python about women. He knows. Did you ever hear the yarn about Athene and Arachne—”

It was the sort of tale men swap over wine cups, and Hephaestus told it well. Peter countered with a milder one. It was new to the smith and he laughed until tears ran down his leathery cheeks.

"Tell me more, Peter. One seldom hears a fresh one nowadays. Have some more wine. Here is a new sort.”

Hephaestus poured out the fresh supply, sampled it and made a wry face.

"Faugh, it has soured! It's the heat. But if I keep it chilled it is too flat.”

"It hasn't got much of a kick to it," Peter agreed. For a moment Hephaestus stared at him, then he caught the pith of the phrase.

“No kick? Ha, that's a good one, Peter! The nectar that I gave Cheiron, how it made him snort and kick!"

"Have you cold water here?” asked Peter.

"A rare spring of it. Not all the fires of Aetna can warm it.

You would think it came straight from the snows of Olympus. I have little use for it, save to quench my hot metal. Why?"

“We have liquor in my country," Peter said, "that may be made from wine, and that has lots of kick. It is not nectar, of course, but it has spirit. We call it spirits.”

The sour wine had fermented. It would be easy to make grape brandy out of it. The process was simple. - Hephaestus could easily contrive a pot still and a coil.

"How do you make it, Peter? I could use some 'spirits,' as you style it. I dare not use nectar while I work in the smithy. I have tried it, and it won't work."

Peter made sketches, described the method. "It should be a slow heat, Hephaestus. The fumes rise through the coil like vapor. And the cold water through which the coil runs condenses this vapor, so that it drips from the end of the coil into another container--and there you are!"

He was finding it hard to keep awake. His mouth opened in mighty yawns, while his eyelids drooped.

"You are tired out, lad. You shall go to sleep. I will have your shoes ready for you before you awaken. And also I shall set up this machine for making spirits. Is there a name for it?"

"A still,” yawned Peter. “Sometimes a pot still."

"Come with me, Peter. You shall not be disturbed."

Hephaestus showed him to a small cavern where soft rugs were strewn thick upon the floor, thrust a burning torch of cedar into an iron ring in the wall.

"I will bring you a nightcap, Peter. Then let Morpheus woo thee. You are a brave lad. If I had a son of my own—“

The divine smith sighed, limped away. Peter was half asleep when he returned.

“This is my own brand of nepenthe, Peter, diluted with wine. You'll awaken a new man."

The liquor was spiced with herbs, and pungent. Peter felt a delicious easement stealing over him. He did not see Hephaestus leave: Once he heard, as in a dream, the clang of metals, the shouting of the fire-master. Then real dreams came to him, in which Ephryne turned out to be Calixta. There was a wedding on Olympus; with Pan playing the march to the tune of “The Kerry Dance." Then oblivion.

PETER AWAKENED with a sense of having slept a week, completely rested and vigorous, with a tremendous appetite. At first he did not realize where he was. He felt for his cigarette case and remembered. Fitful light was playing on the walls of his rock chamber; no noise came from the smithy.

Then Hephaestus entered.

“The shoes are done, lad. My fools spoiled many, but I made them reforge them. Now they can furnish Cheiron with all he needs. And we have rigged the bellows. It works like a spell. You shall breakfast with me, Peter, and then be on your way. The galley has returned."

"So soon?"

"Time passes when you take nepenthe, Peter. Let us eat. And you shall try some of the spirits I have made. I am much beholden to you, Peter. Wait till I introduce this stuff to Olympus!"

The stuff had the wallop of a sledge hammer, combined with the kick of a mule. It seemed to flay the membrane off Peter's throat and sear the lining from his stomach. It needed distilling two or three times more for mortal use, but Hephaestus downed it as if asbestos-lined:

“Do you want some. to take along, Peter? Spirits is a good word for it; surely it is ardent enough to put a new soul into any mortal."

Peter duly thanked his host, said he did not see how he could carry it.

"That is easily solved. I will make thee a flask of metal, with my own hands."

There was no sign of the Cyclopes, the dead guard had been removed.

Peter's bellows had been rigged, and

Hephaestus was as pleased with it as a child with a new toy. Again Peter marveled at his skill as he made a flask, flat and not too heavy, cooled it, fitted it with a twisted plug to a threaded neck, proud of his work.

He filled it with the grape brandy.

"You will find the shoes, nails, hammer and rasp at the end of the defile, Peter. The sailors can carry them to the galley. And I have sent a messenger to Aeolus. You will have fair weather. Give my regards to Pan. He is a mischievous person but a good friend. I doubt if he is as successful with the women as he makes himself out to be. But those matters pall, Peter, when one is immortal. My respects to Hera, my mother, if she condescends to notice you. 'Ware Ephryne! You see, she may have some notion that her fair fame has been tarnished because you have escorted her—”

"She needn't worry about that,” Peter answered. "I haven't got much use for women. Treat them nicely and they think they own you—"

"True, all too true. But she might - have use for you, redhead. And they use tricks like that when they want to secure a mate. Well, go your way. You will always be welcome here. I may see you later, on Olympus. Zeus is always wanting new thunderbolts. I have a new pattern I want to try out. Hail and farewell!”

His grip almost crushed Peter's hand. Then he patted him on the shoulder, stood watching, as Peter made his way up the ramp, the flask of spirits in his hip pocket.

PETER WENT with swinging stride, imbued with vitality. He had established his self-confidence. He had handled the centaurs, got by Scylla, Charybdis and the Cyclopes. He had made a friend of crusty Hephaestus. And he had dodged Amphitrite. Now for the Python.

Before he reached the entry to the rift he heard, sounding distantly, the clamor of the laboring Cyclopes, set again to their tasks, the bellowing of Hephaestus.

In the rift the air was sulfurous, and he was glad when he emerged into the open, filled his lungs with ozone, saw the bright sea sparkling below. The shoes and tools were piled as promised. Peter went on down to where the galley was beached, and Tiphys greeted him as one returning from the dead.'

"A Cyclops waded out to us and drew us ashore," he said. “There were others on the strand, and we thought we were lost. But, though they looked hungrily at us, they did not harm us. They said they said you were a guest of Hephaestus."

"I visited him while he made some trinkets for me," said Peter carelessly, watching the awe in their faces. That would offset the fact that his shadow was sharp upon the sand. "Let us fetch them and set forth. There will be a fair wind.”

There was not only fair wind but favoring current. With these and the oars they made rapid progress.

Peter figured they averaged better than thirteen knots.

Pan, as Hephaestus predicted, was on the shore, stretched out between two rocks, softly piping. Peter whistled the first bars of “The Kerry Dance" and saw him get up, come to meet him.

He looked a bit weary but his greeting was hearty.

“You've made it, Peter. I knew you would. Your friend Pyloetius is hanging around somewhere. You had better see him and send him back for some of his playmates to bring sacks and transport the footwear. Then you can tell me of your adventures.

"He will report your meeting me to Cheiron, of course, and he may. have seen me go into the temple to meet you, watched you leave. It will not matter as long as you got what Cheiron wants. Er-use your own judgment, Peter-but it might be as well not to disabuse his mind of the idea that it was his scroll to Amphitrite that pulled the trick.”

Peter nodded his assent. The sailors were unloading the shoes. Hephaestus had been better than his word. There were five hundred of them in assorted sizes, together with a sack of nails.

"How is she?” asked Peter of Pan. "Who? Amphitrite?"

"Yes. Should I thank her?”

"I wouldn't: I left her asleep. We had a lot to talk about. She wanted all the gossip, some of which I made up to please her. And she had a deep dish of it to serve out herself. She talked me deaf, dumb and almost blind: You must not be offended, but I think she has forgotten all about you. It was your red hair that fascinated her. I'm sleepy myself. I'll wait here while you see Pyloetius. Then I shan't see you again until you're through with Python. If you want me then, play the air of Syrinx."

DOLON stamped upon the rock with his new shoes. It was flint and Dolon chuckled as he saw sparks.

"I feel a little clumsy," he said, “but doubtless I shall get used tothem. They will save my hoofs."

"And mine," said Atocles, his black hide lustrous. "Pick-out a light pair for me, please. I am next. Be sure they are a good fit, and try not to hurt me."

For one long out of practice, Peter felt he had made a good job. Cheiron stood by, benignly stroking his beard.

"Come and eat, Petros," he said. "You have done well. After the meal I will tell you where to find Python. I had to make some inquiries."

When they had finished, they sat at the mouth of Cheiron's cave while the sunset died. It was a smoldering display, with streaks of dull crimson dying slowly amid masses of dark-purple vapor. A fitting background, Peter thought, for the tale that Cheiron told, giving him directions.

"Python lies coiled within a cone-shaped, solitary mount. It once spouted flame and rock, but that was long ago. In it, they say, is a passage that leads by winding ways down to Hades. All about it lies a thick forest. You may know when you approach it by the lowing of the cattle Python pens there to feed

"He comes out only at night, in dread of Athene. Not being sure when Apollo may return. From his mouth he rolls the great jewel and“ by its light selects three beeves. He crushes them in his coils, and when when they are pulp he smears them with saliva. Then he draws himself upon a carcass, as one draws on a glove, moving his jaws forward and back, right and left, with his teeth sunk in the mass. Are you cold, Petros?”

“It did seem to be getting a bit chilly. The wind is sharp."

"Have some more wine, Petros.

When he has them all in his, belly he slides sluggishly back to his cave and sleeps. Should you find him thus, it might be a good time to get the jewel and release the maiden. Without the jewel he is powerless, for he has lived so long in the dark that he is almost blind, and his eyes are partly filmed with horn.

"But his scent is as keen as his hearing. And he is the craftiest of all creatures. Beware, Petros, lest he pretend friendship, and you get too close, so that he may fling a coil about you. You would be but a gobbet to him, but perhaps a savory

"A savory gobbet." Cheiron had much too fertile a vocabulary, Peter thought.

"My advice would be not to go, Petros. If Zeus slew thee, it would be a swifter death-and a more pleasant one."

“Thanks, Cheiron," said Peter, not without sarcasm. "I'll think it over."

He did not want to think it over too much. Now he was upon the final threshold of his task, he felt a definite sense of opposition, the gathering of invisible powers that might be leagued against him. Zeus was pitiless. If his playthings failed, the fault and the penalty were theirs.

But he was going. Python could not be much worse than Scylla, and he had got by that too handy hag. It was on the knees of the gods.

He conjured up all that he knew about serpents, heard or read, and with the stress of the situation a memory stirred in his subconscious, not yet formed,but shaping.

"I will have Pyloetius bear you within sight of the mount," Cheiron was saying. "He did not like the idea, but I have laid my commands upon him. And he has a high opinion-of you, Petros. So have I. When do you want to start?”

The sooner it was over the better, Peter thought. "Early tomorrow, Cheiron. After I have shod Pyloetius."

"Good. Then you will get a good night's sleep before the journey."

Peter doubted it, but to his astonishment he slept soundly until dawn.

PYLOETIUS proceeded, in an easy canter. He had got used to the feel of his shoes, and was now proud of them. But he was nervous and sweating when he halted to point out to Peter the lone cone of the mount, rearing from a dark forest.

"I will take you to the trees," he said, “but no farther, even though Cheiron has me slain. I am deadly afraid of snakes. It runs in my blood."

"I don't fancy them as pets, 'myself, Pyloetius. I don't blame you. You have borne me well, and I will give you a gift, for remembrance.”

Peter produced his pocket lighter, showed the centaur how to manipulate it. Pyloetius took it with profound thanks, with a mingling of awe and delight.

Having no pockets, he kept it close clasped in one hand. “I hope Cheiron will not want this,” he said.

"Don't show it to him, then, Pyloetius."

They went on to the edge of the forest. The wind blew toward them with the clean, pungent scent of resin and fir foliage. There came also the faint lowing of cattle. Peter wondered if Python were selecting a meal.

Then he reflected that it was too light for that.

They shook hands át parting, man and centaur, and Peter watched as Pyloetius picked up speed, galloping his best to reach a safer zone.

Cheiron had ordered a lunch put up for him. It included a small jug of wine. Peter ate his lunch slowly, wondering if it would be his last meal. He preferred to die, if he had to, on a full stomach. He ate and drank slowly, his back against the bole of one of the great fir trees, and longed more than ever for a cigarette.

Thinking and longing did not work with tobacco, he had found out. Pan's cantrips were useless except with affairs natural to the country. The gods had not adopted the solace of smoking, and its, unknown, foreign materials could not be materialized.

No birds sang in the deep wood. Nothing stirred in its thickets. An intense silence reigned. The cattle were quiet.

Peter began to work on the notion that had come into his mind. He took out his whistle and practiced - certain simple melodies. At last he put it away and entered the forest.

He found a path over which he figured the sacrificial cattle were driven. They were votive offerings to Python. He could no longer see the mount for the trees. No sunshine came through their dense foliage.

At length the corral came into view. It was stoutly built and contained about two score of steers that rolled their eyes at him as he passed.

There was a great trough of water, brimming over, fed from some spring that welled in at the bottom. Peter's throat was dry and he drank deeply.

Now he saw another trail, a strange one. It looked as if some mammoth cable had been dragged through the deep drift of fallen fir needles and cones.

A living cable. By this eerie path Python crawled to select his beeves, dragged back his distended length to his retreat.

Peter followed it. He had to keep going. If he once halted, he knew, he would not go on again, for all of Zeus and his thunderbolts. He tried a low whistle, but his lips were parched. He made himself a phrase to which he kept step, repeating it over and over.

"You never are licked till you quit.

You never are licked till you quit.

You never are licked—“

Now the still air held a-reek of musk that gradually grew stronger, more offensive. The forest was shadowless, and so was Peter. But the great serpent was, in a sense; the father of all mankind. No doubt it was Python who had tempted Eve. He could smell out a human mortal, might now know that Peter was approaching.

The memory of Cheiron's description of Python licking his pulped victims, licking them with a forked tongue, smearing them with saliva so they would go down easier, became suddenly visualized, and he shut it off. He took out his whistle, wetted his lips with the last of the wine, piped himself along to the tune of the marines.

“From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli—”

It was a brave tune and it heartened him, marching like an automaton, with the musky reek in his nostrils. Let Python hear him. If Python were awake he would be expecting him. Peter finished the march and started another. It somehow seemed appropriate, the march of the British grenadiers:

“Of Hector and Lysander, and other names like these—

Some talk of Alexander, and some of

Hercules.

Heracles was the more correct. Heracles, who had strangled serpents in his cradle. Serpents sent by Hera to destroy him, Peter remembered. He wished Heracles was along. This was a tough assignment. Peter did not feel scared, but he was definitely afraid he might not be coming back.

Or Pan. But it had become plain to him, before this, that it was expected of him to tackle the real difficulties of his task alone. Pan had gone as far as he dared to help him.

PETER WAS GETTING a bit fed up with caves. Whether this encounter was to be his finish or not, he preferred to meet it in the open. Now.. that he was up against the final cast of the dice of destiny, he no longer felt nervous. He had charged himself with confidence, and a dynamo of resolve and effort was purring away within him. He had accepted the challenge, and his spirit met the issue with the impetus of a thoroughbred, stirred and elated by the presence of odds.

For all that, he liked the cave business less and less as he advanced along the winding tunnel, with its ever-increasing musky stench. This was different from Cheiron's retreat or the sub-volcanic approaches to the smithy of Hephaestus.

It was crudely circular, and the interior almost entirely smooth, glazed by vitreous deposit left by the flow of the molten tide that had issued through the vent.

The intermittent flashes of Peter's torch revealed the glaze to be darkly iridescent, like the matrix of black opals, with hidden gleams of red and green that glowed with a weird beauty.

It sloped gently upward in long curves. The air was sluggish, heavy with the reptilian odor, sometimes. curiously misty, then radiantly clear.

Presently Peter became conscious of a hissing sound that slowly increased in volume. It was like the escape of steam, but Peter believed it to be the voice of Python, resentful of an intruder.

It was time, he thought, to test the notion that had come to him. Some serpents could be charmed by music, were susceptible to its vibrations. Snake charmers could control hooded cobras, put them in a trance.

It was one thing to tame a cobra; it might be quite another to affect such a monster as Python. At the zoo they had found boas responsive to organ tones, but they were worms beside this primordial creature that, somewhere ahead of him, stretched its scaly fathoms.

He should have asked Pan about it, but the notion had come too recently. He brought the beam of his torch to a minimum, tucked it under one arm, and set his pipe between his lips, fingers on the sound holes. He had brought along the leather bag in which he had carried his luncheon. He had a definite purpose for it, if he got the chance to use it.

Peter was no composer; he had to choose tunes he could manage as an amateur. He must attract Python's attention, distract it from anger. A lively air at first, he thought, then soothing ones-lullabies might be best.

His pulses kept rhythm to the lilt of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” then "Tipperary.” The act of playing held him to his own purpose as he marched, the bright bead of his light slipping over the curves of the tunnel. The hissing died down. The effluvium of musk lessened, as if Python had been emitting it in an anger now subdued.

So Peter hoped, and kept on piping.

Now he heard a rasping, rustling noise. It was like the sound of heavy chains dragged over a grid. It might be Python stretching his convolutions--it might be "Python approaching.

The sibilance had ceased entirely. He rounded a curve. The ray hit first one, then another, disk of light, throbbing orange with shifting spots of blue, the color of burning alcohol. It was infinitely baleful, abhorrent, that steady, hypnotic glare, intense with sinful wisdom. It was a hot gaze, seen like furnace fire through plates of isinglass or horn.

Had the enormous eyes been unfilmed, Peter felt they might have shriveled the soul within him. But long living in the dark had bleared them with a cataract growth that dimmed their malignance.

They hung in the air like great, murky lamps, suggesting brilliant lights back of dirty lenses.

PETER TUCKED his whistle away in his belt, adjusted the lens of his torch to full focus. If he could not dazzle the monster, as he had the Cyclops, he could prevent it from seeing him, back of the cone of illumination.

And now he saw the flattened head, enormous, the gaping jaws wide apart, set with rows of back-hooked teeth, the maw that could engulf the carcass of an ox. A pinkish-yellow tongue, forked and vibrant. Back of that, the sinewy column of the enormous neck, and hinted coil after coil, trailing into darkness.

The orbs were unblinking. Slowly they lowered—lowered until the ophidian head touched the floor, while a slow rustling proclaimed the adjustment of its body.

Peter gaped and gasped as an intense roseate light came from Python's gullet. It moved forward, rolling between the shark-like but elongated teeth, over the bony plates of the lower jaw, like some will-o'-the-wisp of Hades.

Python was ejecting his magic lantern, the great jewel Hera coveted. The tongue rolled it forward but it seemed to move of itself, automatically. The color was that of an unflawed pigeon's-blood ruby, a globe haloed by the mystical luminosity within it. It was almost as large as Peter's head; its exact size and shape hard to determine because of the aura.

Peter's electric ray was blanched by it. It filled a great space with its roseate radiance, softly intense, light without warmth but suggesting it. It was not so brilliant as diffusive—all-revealing.

It rolled a short way from the jaws that closed behind it, the jaws of some legendary dragon beast, and lay like a Promethean spark, while Peter switched off his futile torch.

Then Python spoke.

It was a voice infinitely wise and infinitely weary, like the voice of Satan. Peter heard its echoes dying away behind him in the cavern's tube.

"Oh, ho, a mortal! I smell your blood! Now, by the heads of Cerberus, what brings you here? What courage sustains you to venture into my retreat?"

Peter found his voice. Python was yawning. He was bored rather than menacing, mildly intrigued for the moment, rather than malignant.

"I come seeking knowledge, O. mighty Python!”

"Seek it at Delphi, mortal, or has the sibyl forsaken the shrine, since I no longer guard the oracles?"

"Mortal though I am, I have enough of wisdom to desire more from its fount, O Python!".

Python yawned again. He seemed amused at Peter's temerity, though it might be only in cat-and-mouse fashion. If he were asked what questions he wanted solved, Peter would be in a quandary. He had a vague idea of asking Python just what fruit it was that Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge. He might not be able to jolly Python as he had jollied Hephaestus.

But he was not put to it.

"I do not feel like answering questions, mortal. My change is upon me. I would not be disturbed. I have suffered your approach only because of the dulcet notes I heard.. At first I thought it was Pan. Music is at once my bane and my delight. Surely Pan taught thee, mortal? I would hear thee play again.”

""Pan is a good friend of mine," Peter said.

There was never any harm in mentioning the name of an influential and important personage.

PETER wondered what Python meant by his "change." Obediently he began to play the airs he had selected for this ordeal. The head of Python lifted, swayed gently to and fro. His baleful eyes began to close: Once his forked tongue slipped out between the horny lips and licked delicately over his nostrils while Peter fluted: "

Go to sleep, my li'l pickaninny,

Underneath the silvery, southern moon,

Hushaby, rockaby, Mommy's lil baby,

Mammy's li'l Alabama coon."

It seemed childish, infantile, getting the King of Serpents to rock himself to sleep with simple lullabies. It was the suggestion of the drowsy rhythm that held the sleep-inducing power and it was working.

It was almost ridiculous to see Python yawn, nod, yawn again, save that this was all in deadly earnest. The mystic jewel lay in front of Peter-somewhere in the vastness beyond was Ephryne.

This was simple stuff, but it was magic-universal magic, a gift of the god's to man as great as fire.

"Go to sleep my ba-a-by, my ba-a-by, my

ba-a-by”

Then:

"Baby's boat's a silver moon, sailing in the

Sky—“

Python's head lowered once more; it rested on the floor, eyes closed. Python had eyelids like a man..

Peter sounded “Taps.” He played it with feeling, compellingly.

"Go to sleep! Go to sleep!"

Its spell lay upon the gigantic serpent. As Peter softly fingered the last phrase

"All is well!”

—he saw that his magic had prevailed. Python might have been a stuffed exhibit, without sign of breathing, of life.

How long that hypnosis might last Peter could not guess. He hoped it had only accentuated the drowsiness that had already possessed Python, something, perhaps, to do with the “change” that was upon him.

Silently, swiftly, Peter opened his leather sack and rolled the glowing gem into it, drawing tight the strings. It was not a heavy burden, and he took it with him as he switched on his torch and stepped lightly along the-relaxed length of Python.

He had an idea that Python was not well, though it might have been age that robbed his skin of all gloss, made the 'scales look dead. He wasted little speculation on that as he stepped off, fathom after fathom, and at last passed the slowly switching taper of Python's tail, the only suggestion of vitality in the whole torpid trunk.

The tunnel grew smaller, still mounting. It seemed to extend into the very womb of the mount. This might even be the regular byway to Hades. By now he had left the stink of musk behind. The air was purer and in motion.

Then an opening appeared, branching off like horizontal wells of mystery.

Where to find Ephryne? How to find Ephryne?

He had the gem, if he could get out with it. The task was better than half done.' Zeus wanted the jewel. But he had included the request. of Leto, grandmother of Ephryne. And Leto, Peter knew, had been the first consort of Zeus, though Hera had managed to supersede her. She might still be the favorite wife, for old time's sake, if Zeus had a favorite.

Peter doubted that. The domestic virtues seemed no part of Olympian culture. It must be a bit wearying, he thought, to see the same face or faces--across the matutinal nectar and ambrosia for eternity."

And Zeus would not sanction a task half performed.

PETER BEGAN to pipe again, gave that up to call upon the name of the daughter of Artemis. He could not hunt her down all these Stygian corridors. His electric torch was beginning to wane. The batteries were depleting. They would not last much longer.

True, he had the roseate jewel, but its approaching light might only terrify the captive maiden. He wondered how Python held her prisoner. If chained to a rock, like Andromeda, Peter would prove a futile Perseus. The file Hephaestus had given him, which he had left with Cheiron, might come in handy--if he had it.

And Python's "change” worried him. When it came, what would it portend? What would happen when Python found his magic light was gone? With his marvelous olfactory sense, would he not come gliding and hissing on the trail of mortal blood, Peter impotently fleeing—

Peter flashed his paling torch into one of the side, chambers and saw what seemed to be a girl's form, prone on a narrow shelf. But it was only a husk of the elusive, maid, a diaphanous garment flung aside. He hurried on.

Singing, above him, close at hand. He halted, listening:

"When comes he, my hero,

To carry me hence?

Away from this creature

So scaly of feature,

When comes he, and whence?"

It might be lyric verse, he thought, but as poetry it was definitely bad. And the voice, while it had its sweetness, failed to keep on key. The effect was appealing but hardly sirenic.

"Artemis, my mother,

Give ear to my plea,

Oh, hast Thou forgotten,

Thy babe-god-begotten?

Have pity on me."

It was Ephryne, all right, a bit euphemistic about her other parent—

"Arouse, my deliverer,

Where'er he may dwell,

O, send him here fleetly,

That he may completely.

Break Python's foul spell.

"O, haste Thee, my hero,

To greet Thee I pine,

And all of my beauty

Shall yield you sweet duty

And Thou shalt be mine."

To Peter it was a pitiful plaint, in more ways than one. He was not enthusiastic about the implication of the last stanza. Ephryne might be merely indulging in poetic license, but it looked like still another complication looming ahead. When a goddess was grateful to a mortal, and wished to bestow favors, the affair was apt to be chancy. To refuse might bring on dire consequences. And if the goddess grew tired, or the mortal failed to live up to her divine expectations, trouble was right around the corner, and more apt to turn it than prosperity.

There was no help for it. He went on a little way, let his ray travel ahead to where the tunnel widened and heightened. The singing stopped. He called her name: "Ephryne!"

He heard a gasp, caught a glimpse of a head, running over with golden curls that were a bit tousled, peering down from a ledge.

“Who art thou? Did Artemis send thee?"

“It was Leto, through Zeus. Come on down. We've got to get out of here."

"I can't. Python has taken away all my clothes. Have you slain Python? Perhaps, if you extinguished thy lamp—”

“I have charmed Python to sleep, Ephryne.” That might be stretching it a bit, but Peter felt he was justified. "I know where your clothes are. I will fetch them. There's no time to lose. I can't tell how long my spell will last."

"Oh, hurry, hurry! But firstturn thy light upon thyself.”

That was fair enough, Peter thought, and did so. He heard another gasp.

"Ah, now I know you are a favored son of the gods. I adore your hair. It is divine! It burns like an altar flame."

"I am not divine, Ephryne"Peter almost said "sister” in his embarrassment. “I am but a mortal, though dispatched by Zeus to rescue you."

"A mortal! Oh! But Zeus shall make you immortal. Leto shall ask it of him. It shall be a part of thy meed. And I—

I've got to go," said Peter. “I'll be back in a jiffy."

He sped away. Not if I know it, he promised himself. Immortality is OUT.

He found the clothing, laid it be low the low the ledge.

"I'll leave them here while you dress," he said. “Call me when you're ready."

The goddess giggled.. "You're nice," she said. “Tell me your name.” She had dropped the unfamiliar "thee" and "thou."

"It's Peter. But hurry."

"I like it. Do you like my name, Peter? Now go away-not too far. I don't think I ever want you to go far away, Peter, now you have found—

SHE MIGHT turn out to be another Amphitrite, less forward, since Amphitrite was married. I've got to get hold of. Pan, toute suite, thought Peter.

"Here I am, Peter. Didn't I dress' quickly?" A soft hand slipped into his. She took the torch away from him and turned it on herself. It was no wonder it had taken her a short time to dress, Peter thought. The costume was briefly provocative. The blue eyes were at once appealing and mischievous. Ephryne was shapely but a little on the robust side—voluptuous might be a nicer word.

"Am I not beautiful, Peter?”

"Too beautiful for mortal eyes."

"Oh, Peter, you do say the sweetest things. But we shall arrange all that. Put your arm about me, Peter. I shall-feel safer, and we can go more swiftly."

You bet your sweet life we can!

It was not only the urgency of getting out of the mount, out of the forest, that urged Peter on. Ephryne had possessive ways. She seemed to think she owned him already.

"What's in the sack, Peter?"

"Python's jewel."

"His je— Peter, you are marvelous. Let me look at it."

"Not now.”

“Just once."

"No!"

"I command thee, mortal."

"I tell you there's no time. Come on.”

"So masterful,” he heard her sigh.

And then he heard the sibilant hiss of Python, awakening, missing his treasure.

Ephryne clung to him, shuddering.

Peter could not blame her for that: She kept timidly behind him as they advanced, and Peter risked using his feebling torch.

It showed the powerful body of Python humping in convulsive undulations, seeming to constrict every muscle and then violently relax. It was not for the production of motion. It seemed rather as if the mighty snake was stricken with terrific pains that racked it from lips to tail tip.

Python writhed from side to side, went through all the antics reported by discoverers of sea serpents, as illustrated by imaginative artists. It might, Peter fancied, be some sort of ritual, a frenetic dance for which he was practicing, keeping himself Jimber against the time when he could square things with Apollo and return to his job as guardian of the shrine of the sibyl at Delphi.

But Python had spoken of a "change" and this must be it.

The hissing grew louder, like the escape of steam from a cylinder that was overcharged. In pain or not, it was clear that Python was making prodigious efforts, threatening to tie his length in knots.

They dared not try to pass him in the narrow way as he flung himself from side to side.

The flash torch was fast fading out. To use the jewel would surely direct Python's attention and wrath upon them

Suddenly Python lay flat, at full length, exhausted and quivering, as if gathering strength for the next contortion.

And Peter saw what it was all about.

The dull skin, with the dead-looking scales, had split down a part of his back, where a snake's shoulders would be, when snakes had shoulders.

The rent revealed a new and lustrous armor, burnished and metallic.

Python was shedding his skin. Having a hard time to do it. But, once started, the rest should be easy. And, with the shedding, his blindness might disappear. That was snake history. There was indeed no time to lose.

This time it was Peter who grasped his companion by the hand and urged her along. As they passed

Python's head it jerked from side to side, but Peter did not think he could see, smell or hear while the change was on. He had no true knowledge of herpetology, but he had some hazy ideas about what went on at such times. Those ideas included the statement that snakes were most vicious then, lashing out blindly.

They, tiptoed past, in safety, as the convulsions began again. They left Python writhing violently, intent upon his own condition as they fled into the forest, down his trail, past. the cattle corral, without stopping.

Nor did they halt until they got out of the trees. Peter was winded, but he saw that the daughter of Artemis, albeit plumpish, was not distressed. That, he supposed, might be an attribute of the gods. She cuddled up to him.

"That was a fearful spell you set upon Python, Peter. Will he die?”

"Not this trip, Ephryne." If she thought he had made Python's skin split up that way, let her do so.

"Now let me see the jewel, Peter."

PETER TOOK it out of the bag. Dusk was coming on, but the radiant glory of the mystic gem banished it.

A rosy glory, the light that never was on land or sea, filled the world, limned the tall tree trunks and the dark foliage, made Ephryne look like Aurora herself.

She could barely hold its bulk in her two-hands.

"Hera will use it as a scepter," she sighed. Peter took it away from her. He saw. a covetous and calculating look come into her eyes, something that needed nipping in the bud. Something that gave him additional insight into the nature of Ephryne. Goddess she might be, but she was a greedy brat, probably spoiled. What she wanted she reached for.

The look became petulant as Peter put away the jewel from sight. Some of it returned as she looked at Peter. But it was petting now instead of pettish. He remembered Pan's promise to show up, if wanted, upon signal.

"Shall I show you how. I laid the spell upon Python?” Peter said guilefully.

“I should love it, Peter."

He took his whistle and played “The Kerry Dance." Played it twice. Ephryne listened with her head on one side, her lips pursed: In the twilight she looked very charming. There was a certain glamour about her, a certain—

Peter heard a familiar, welcome chuckle. Then Pan leaped out of the forest, landed lightly, stood there quizzically regarding them.

Ephryne pouted. “What is he do ing here, the smelly thing! Get him to go away, Peter.”

"I couldn't do that. If it were not for him, we should not be here."

Ephryne made a sour face and Pan scratched his ribs.

"I see you won out, Peter," Pan. said. "I knew you would."

"He is wonderful,” Ephryne put in. "I am going to get Leto to ask Zeus to make him immortal. Then he shall wed with me.”

Pan winked at Peter in the growing gloom.

"How did you' manage Python?” he asked.

Peter told him briefly and Pan laughed until he had to sit down to finish it. Then he got serious.

"If he sheds his skin, and with it his blindness,” he said, “it might not be too healthy for you round here,

while you are still mortal. You were certainly in luck. Python renews his skin only once in a hundred earth-years. He may not stay in hiding any longer and, eyes or no eyes, he is not going to take the loss of that jewel lightly. Nor, of course, the loss of Ephryne, who was his hostage. I think we had better be on our way."

There broke out a sudden bellowing of cattle back in the forest. They knew what that meant. Python was coming, swift in his new armor.

It was almost dark, the stars pricking through.

"I doubt if his night eyes are much better than ours," said Pan. "He'll rely upon scent. I brought these with me, in case. Break out the cloves and rub your feet with them. On your shoes, Peter, well up. You, too, fair virgin, unless you want Python to infold you."

Peter took the small bulbs Pan offered him. They looked like garlic, smelled like, garlic—they were garlic. Ephryne sniffed disdainfully.

"I will not defile myself with this stuff," she said. "Python may not harm the daughter of Artemis! He would not dare to try."

"I'm not so sure about that,” said Peter. "And Python's own smell is not that of asphodels."

She hesitated. Peter was already rubbing his shoes. They were field boots, and he smeared the juice of the bulbs high to his knees. The pungent scent of the oil enveloped them.

He knew that garlic would foil bloodhounds, and that it was supposed to have magic virtues over ghouls and werewolves, a virtue that probably lay wholly in its power to surmount human odor.

THE BELLOWING of the cattle redoubled. There was a crashing sound, and then bullocks came tearing through the trees, snorting in terror. They had broken down their corral. Now they heard the hiss of Python.

"I smell of it already," cried Ephryne, her voice tremulous. "Help me put on this dreadful stuff, Peter."

Python was coming, winding through the wood. The hissing ceased. He was moving silently.

"Come," Pan said imperatively.

"Take her other hand, Peter.”

That was more to force her movement than needed assistance, Peter realized. She went as a daughter of Artemis should, like a deer. Pan like a mountain goat. Peter was hard put to it to keep pace with them. Pan guided them as they fled through the darkness, away from the bolting steers.

Peter glanced back and thought he saw the gliding length of Python, crest erect, emerging from the trees.

Then they plunged, bounding, into a dell, splashed through a knee-deep stream, sought covert in a thicket of the sacred laurel. Peter was panting like a blown runner after the final sprint. Ephryne was far from winded.

Pan breathed easily. “We are safe here," he said. "I'll scout when the moon rises. All this has happened. at an opportune time, Peter. Zeus has been playing truant again, and Hera's pet, Iris, has been, as usual, spying and carrying tales. The jewel will be a welcome diversion. Presently I will anoint you with ambrosia, Peter, and then we can speed to Olympus. I could hardly have done it in time back there, not to mention the presence of the lady."

"You two could have outstripped Python," said Peter, “but you stayed with me.”

"Didst think I would have left you, lad?” Pan's voice was strong with affection. He slid a hairy, muscular arm about Peter's shoulder.

"Or that I would, Peter, my rescuer? I shall never leave you, Peter, never. We shall be together, when we are wedded, night and day—for always."

Peter thought, The heck you will! and heard Pan's chuckle. He had forgotten Pan could read his thoughts. To his relief, Ephryne did not seem to notice anything.

The moon lofted and Pan stood up. "I shall not be gone long," he said.

Peter knew Pan caught his silent plea to hurry.

Ephryne put her soft arms about him, pressed her cheek to his. “You must promise me, Peter, when Zeus has granted my boon, and we are truly one, not to have anything more to do with that vulgar person. Kiss me, Peter."

Peter almost groaned aloud. He had known this was coming. And he again remembered Calixta.

He was aware that his response was pretty tepid, would probably be considered amateur by the average girl who made an advance. As for her offering, he decided that the kiss of an ardent and grateful young goddess was not to be entirely despised. But he was not going to get hooked, to find himself pledged to matrimony, Olympian or otherwise.

She looked at him curiously.

"Do mortals. kiss, Peter?” she asked. “You do not seem to know much about it. I shall have to teach you."

"Listen," Peter stalled. "Was that Python hissing?”

It was not, but it distracted her mind, or her lips. She began to tell Peter all about herself; she prattled and babbled until, to his infinite relief, Pan came back. ..

"Python is headed for the sea," he said. “I saw him going, rippling himself like a wave, his new skin shining. But he'll find out his mistake and it's time we were going. If you'll take a walk, Ephryne, I'll give Peter his rub."

She rose with a pout and a shrug. "I'll give you your rubs, Peter, after we are wed. I just love to have my back rubbed.”

Pan started to chuckle, and she gave him a look that might have turned him to stone, had she the. power.

VIII.

OLYMPUS was effulgent. Radiance seemed to issue from within the mountain to blend with the sunshine pouring from a cloudless sky. A gentle zephyr carried rare essence of ambrosia and lightly caressed the trees, the grasses, the flowers and verdure.

Zeus and his court were assembled. Cupbearers passed among them, and Hephaestus himself was there, hobbling about and superintending the libations.

The immortals seemed happy, but Peter fancied they were putting on a show that had been played too often to retain much spontaneity. His arrival with Ephryne and the jewel had made a stir. The gem seemed the more important for the time.

Ephryne was with Artemis and Leto, talking, chattering. Peter was glad to be rid of her, for the time. at least. She had talked at full length about the vows they would plight, that Zeus would solemnize and sanctify, his own immortalization, the elaborate ceremony that would plight them to each other"for · ever-and-ever-and-ever, Peter darling."

Apollo would give away the bride. The Muses and the Graces would be bridesmaids. All the notables of Olympus would be there. “Oh, Peter, just think of it!"

He did think of it. He was thinking of it now as he stood with Pan. on a lower terrace, where the gods lounged, regarding him, awaiting the report of the red-headed mortal who had succeeded in the task set him by Zeus. It was rumored that he was to be immortalized, and that he would wed Ephryne, whom he had rescued from Python—as was right and fitting.

It was also rumored that this redhead had an amusing tale of adventure to tell, a second Odyssey.

He walked out on the sward that lay like a thick green carpet before the throne of Zeus and below it. Pan was beside him. There was a special excitement still going on among the consorts of Zeus, Metis, Themis, Eurynome, Demeter, Mnemosyne and Leto, each seeming to envy Hera the magic gem.

Pan pointed them out to Peter, while they waited for Hermes to start the program at the nod of Zeus. The presentation of the jewel that Peter still carried in the leather sack was the first event. Peter was to describe his adventures next. Then Zeus would reward, him. Hermes was master of ceremonies.

Pan showed Peter Artemis, leaning' on her bow, aloof.

"She'll not be sorry to get rid of that daughter of hers, I think, Peter," Pan said mischievously. He knew Peter's ideas in the matter, and the plan Peter had conceived, to which Pan had promised to lend his aid. aid.

"She hasn't got rid of her yet."

Peter muttered, "and she won't-to me.”

"Don't think too loud," Pan warned him. “They might hear you. Here comes my father."

HERMES bore a platen of crystal in which Peter was to place the jewel. He might not himself come too close to the glory that was Zeus lest, like Semele, he might be destroyed by contact with the power that Zeus emitted-too great for mortal flesh to sustain. Hermes would present the gem.

Used to wonders as they were, a murmur of admiration arose when they saw the wonder of the gem, vivid as the living blood of doves, a soft yet brilliant sphere of ruby flame. Zeus approved it with majestic nod, and bade Hermes. offer it to Hera, who took it with a proud delight that made her handsome face really beautiful, tinged as it was from the reflection of the jewel..

The other goddesses gathered round, exclaiming, until Zeus lifted his hand. Hermes, called for silence.

"Speak, mortal. Tell us of thy experience. Then crave of me thy boon, and it shall be granted, what ever it may be.”

Peter saw Ephryne start forward, tug at her mother's arm, turn to Leto, and for one moment he feared she might forestall him. But even Artemis had been charmed by the gem's magnificence. She wanted to hear about it, and she shook Ephryne off.

"Don't be too modest," Pan had counseled Peter. “Lay it on thick, lad, except about Amphitrite. It's a wonder she's not here today. Poseidon must have returned. Play up the rest. Outdo Odysseus. String them all upon the thread of your tale."

Peter spoke up boldly. He did not boast; but he made the most of the perils he had encountered and overcome. He left Pan out almost altogether, as he knew the goat-god desired. The horseshoes went over well, and he made a great hit of his adventures with Python. There was a murmur' of applause that meant a lot, for Olympus.

Peter knew what was the matter with the gods. They were bored. They knew it all, they had tried everything, and the zest was out of immortality.

Nor did they longer rule supreme over the mortals they could embroil, play with as children play with toy soldiers. Mortals knew other gods. Some of them even thought they were gods. But Peter had been a novelty.

Hephaestus limped forward. "It is true," he said. "All that he hath told of me. A likely lad, with a rare wit. Grant him his boon, O Zeus!"

"Speak, mortal. I, Zeus, have given my promise."

"O Mighty Zeus, Supreme Over All, thy humble servant begs this boon, though it has been high reward to serve thee. Yet am I weary and withal bewildered. Being but mortal, it is a strain for me merely to behold thy magnificence. I am but the clod at thy foot, O Zeus. Suffer me now to return to my own people, to my own land, where all the glory of thy realm may abide within my memory, and I shall not be overwhelmed, O Thunderer, for in thy presence I am as one who gazes into the eye of the sun and may not bear it."

Zeus stroked his beard and looked at Hera as much as to say: "You see?” He stroked the head of the eagle that sat on the arm of his throne.

"Thy boon is granted, mortal. Return."

There was a commotion where Ephryne stood, talking to Artemis and Leto.

Pan edged Peter was his elbow. "Let's scram," he said.

THEY moved off without undue speed until they were clear of the lesser courtiers. They went down from that terrace to the next, trying to avoid the appearance of too much haste.

"That was a fine speech you made to Zeus," Pan said.

"I thought it was pretty good myself. Do you often use the word scram, Pan?"

"Why not? When one is in a coil, and sees a chance to scramble clear, it is a good word, surely."

There came a call from behind. Ephryne's voice. "Peter—come back. Peter!"

"We don't hear them," said Pan. “Unless you want to go back.”

"Me?' cried Peter. "Go back and marry that nitwit, that clacking windmill? Pan, she makes me sick. She's like a diet of too much honey. Go back, and get immortalized, and then have to listen to that tongue and see that face every morning for ever-and-ever-and-ever, Peter darling,” he mimicked:

"Not me, Pan. A mortal life would be much too long for that."

Pan chuckled. "I agree with you, Peter. One reason why I have never wed. But Artemis isn't going to take it nicely. Nor Leto. Look out!"

There came the twang of plucked sinew, the 'humming whine of a feathered shaft. Pan had tripped Peter, flung him to the ground, and he saw the arrow of the goddess bury: itself halfway in the turf ahead of him.

Pan was up, yanking him to his feet again.

"Come on. Zeus won't let her shoot again right away, since he gave you permission to leave. But she'll be on your trail for jilting her daughter. It reflects on her. I've got to hide you where she can't turn you into a stag, hunt you with dogs:”

They ran together, and for once Peter kept pace with Pan, expecting each moment to hear the whispering rush of another arrow, feel the shock of it as it sank into his flesh.

They dived into a thicket. Peter could hear the hubbub going on above them, the shrill voices of angry women predominating.

"I have it," Pan cried exultantly. "It's not far. We'll make it. But I'll have to carry you, Peter. No time for a rub, and you can't run fast enough. Artemis will be coming." That was a far wilder ride than Pyloetius had ever given Peter. He clung pick-a-back, legs about Pan's hairy hips, arms about his neck, while Pan went bounding with great leaps through the bracken and the growth that was fortunately well above their heads.

"She's a mighty huntress, but we've got a good start. She'll never find you. Old Pan knows a trick or two. We're almost there."

They left the thicket, and Pan went leaping up a hill where oak trees grew in a stately grove. At the foot of one of them Pan set Peter down. Pan's. barrel of a chest 'expanded proudly, with no sign of distress for that mad race. He took his Syrinx—and Peter suddenly remembered his own whistle. It was : gone. He must have lost it when.. they fled from Python.

"I hope she's not out,” said Pan, setting the syrinx to his bearded lips. "She's a good sort."

Peter was quick on the uptake. "You mean Echo?" he asked.

Pan shook his head. "Not that lovesick little fool,” he said. “She's crazy. over Narcissus, who is crazy. about himself. This is Phela, a far more understanding creature. This is her tree."

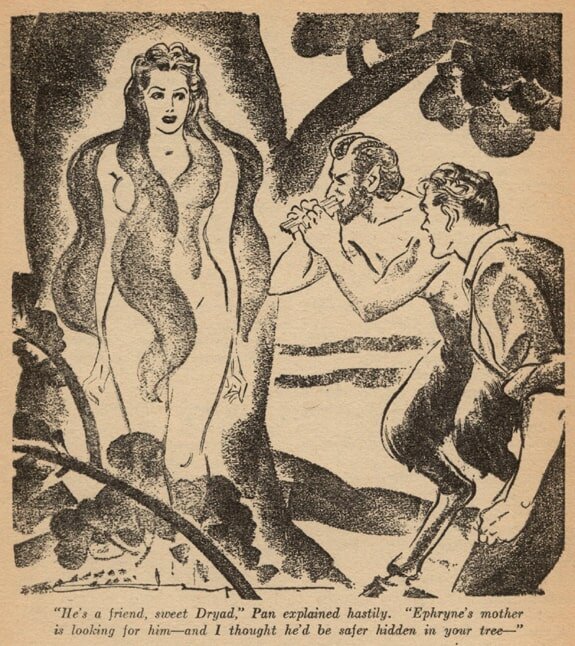

PAN BREATHED his call, strangely sweet, enticing. It was enough to conjure the demurest of dryads, Peter thought, watching a warm glow spread within the trunk of the oak, making it half transparent. Within he saw the shape of a woman, gradually becoming more plain. The rough bark of the oak seemed to dissolve, the bole parted, like a pliant curtain, and Phela stepped forth.

She wore no clothing, but her beauty offset any idea of nakedness. Her skin was the hue of oak leaves in the fall. She had a chaplet of wild vine about her head, and her long hair half clothed her in a mantle with the sheen of satin. Her eyes rested on Peter, turned to gaze at Pan with fond regard.

"Phela," said Pan, "I come to ask a favor. Let this lad stay within your oak. He has done no wrong, but he has displeased Artemis. She seeks to slay him."

"Artemis is cruel. She kills the wild' things of the wood for wanton sport. Your will is my will, O Pan.”

Phela turned to Peter. “For a friend of Pan I will do aught in my power,” she said in her soft voice. "Step within."

Peter did so, and found himself in the heart of the tree, a cavity lined with silken fibers. The rind of the oak closed, and its glow died down. He was left in darkness. He could hear the soft sough of leaves overhead, distinguish the voices of Pan and Phela.

"She comes, Phela. Away with you. Stay near, but do not let her see you."

Pan was playing on his pipes as Artemis arrived, vengeful and suspicious.

"Where is the mortal who has dared to slight my daughter, Pan? Your protection shall avail him. nothing."

"I had the idea he was under the protection of Zeus, Artemis. I. thought I heard words to that effect.”

"Zeus will not stand between me and my vengeance. You are sly, Pan, but beware of angering me."

“The lad is far beyond thy reach, Artemis. He has not passed this way. As for your ansger, I do not give a snap of my fingers for it. I may be sly, Artemis, but there are times when I have been discreet. The wild creatures that you hunt have eyes and ears and tongues. They are my little brethren and they have slight love for thee. Olympus will soon forget this mortal, who wisely feared to mate with Ephryne, but it might not forget some things I that I might whisper in their willing ears."

Artemis' voice' was harsh, with fury.

"You are a gossiping old goat. I've half a mind—”

Pan gave out a jeering bleat.

"You footless, fool!" Artemis answered. "Gossips are like frogs that drink and talk."

"Going so soon, Artemis? Well, good hunting."

Pan started to play again. Peter guessed the irate Artemis had gone. The piping kept on for a while, and Peter grew drowsy. The soft lining of the dryad oak took him into it's embrace.

When he awakened a breeze blew on his face. The oak had parted. He stepped out and saw Pan with his arm about Phela. He saw stars shining through the trees.

"I shall return, Phela. I swear it by the sandals of my father, Hermes. Stay in thy tree, fair nymph."

Pan tapped Peter on the shoulder.

“One last ambrosial rub, Peter. Then you'll be on your way. Didst hear me get rid of Artemis? Achilles had a vulnerable heel. Her weak spot is her reputation. She's a good deal of a snob, is Artemis."

"I FEAR I have nothing to give you but my thanks, O. Pan!"

Pan laughed. He and Peter stood once more before the high hedge of laurel, sacred to Daphne.

"Pan desires no reward, lad. But you might tell your people that Great Pan is not dead! I grieve to part with thee. Thou art well quit of that Ephryne. She will not improve with age. And once they begin to get jealous-look at Zeus. If you ever wish to return, come to the shrine of Hermes, sound the air of Syrinx, and I shall let you through the laurel once again.”

"My thanks to thee, Great Pan! But never while Ephryne is unattached.”

Suddenly he thought of the flask Hephaestus had given him. He drew it from his pocket.

"This is liquor, as we make it in my country, Pan. I showed Hephaestus how to brew it. It is but a paltry gift."

"I was just wishing, lad, we had a lap of nectar.”

Pan unscrewed the plug, smelled, tasted, poured a libation on the earth, tilted the flask.

Peter watched him swallow, marveling.

"Wow!"

Pan spluttered breath of brandy on the air. Once more he applied himself to the neck of the flask.

"Now, by all the gods, Peter, that is a drink! Whooroo!"

The laurel was already shivering. Pan stood with his goat legs well apart, yellow eyes shining. He waved Peter a farewell.

The laurel closed behind Peter. In front of him was the ruined shrine.

“WHOOPEE!" Pan had finished the flask of brandy, Peter heard the tattoo of his hoofs as he tap-danced on the turf, went leaping off. "Whooroo!" Then came the lilt of the Panpipes, missing some notes, but fluting merrily:

PETER FELT in his pocket. The little ivory hippos was still there. The moon was low and the stars were paling, but there was light enough to set, the offering back where he had found it, in the crevice.

As he did so, the lizard shot out, leaped to the fallen Hermes.

This seemed the right thing to do, Peter reasoned. It was his link with the past he had surrendered. Now he was back in his own dimension. He had to reorient himself.

Burton must have given him up for lost, or dead, long ago.

He tried to figure out how long he had been away. It was not easy. Earth days and Olympian days might rate very different calendars. But there had been so many nights so many days.

Instinctively he started for the camp site. It was less than a mile away. Of course, Burton might have left some sort of message for him to find.

There came, a low rumble of thunder, over Olympus way. A jagged streak of lightning.

The harsh bray of a jackass. Ajax! By all that was holy, Ajax! Defying the lightning!

The tent was still there! A light showed through the canvas-a shadow that emerged.

"Peter! Where in Time have you been? You had me worried. I've been hunting for you ever since supper. I had made up my mind to find someone and organize a search for you. I was afraid you'd fallen into some ruin. What happened? Did you get lost?”

Peter was confused. Where in Time had he been? According to Burton, he had been missing less than twenty-four hours. He felt his chin. He needed a shave all right, but not more than usual of a morning. He could not remember having fallen asleep at the shrine. Where in Time—

"Not hurt, or sick, are you? You must be starved. I'll rustle you some grub."

"No, thanks, I'm not hungry. You were right. I—just got lost."

“Well, you're back now."

"Yeah, I'm back."

He had given Hermes back the ivory hippos. Pan had the flask of Hephaestus. Pyloetius had his lighter. Or had he dreamed that? No, the lighter was gone—

"I'm a bit tired, old chap," he said to Burton. "Think I'll turn in. But first, give me a cigarette, will you? I'm all out of them."

END